It’s been a while since my last post. The Gazebo adventure is still alive and well, and we’ll come back to it, but for now, we’ll take a brief detour. We’ll consider an essential topic that doesn’t have to do directly with Gazebo, but it’s still relevant to simulation. We are going to go through a mini-series where we examine the power of parameters in a robotics system. There is an accompanying repository which you can download so that you can follow along.

Some of the core features of ROS that helped to shape it as a robotics framework are portability and parameters. Let’s take a closer look at each of them.

Portability

How is portability facilitated? We can adjust a piece of code from one system to another in several ways. Let’s assume we have a package ros_parameters and a node camera_node_0 that publishes an image to a topic. We can run the node in a terminal with the following command:

> rosrun ros_parameters camera_node_0

This will start a node with name camera_node which will continuously publish a static image on the /camera/image_raw topic. Let’s now use launch files so that we make our upcoming changes persistent. With every example, we will run a launch file like this:

> roslaunch ros_parameters bringup_X.launch

but inside each file, we adapt the node as we like. We can

- change the node name (

camera_node -> camera_driver):

<node name="camera_driver" pkg="ros_parameters" type="camera_node_0" />

- set a namespace (

camera_driver -> robot_0001/camera_driver):

<node name="camera_driver" pkg="ros_parameters" type="camera_node_0" ns="robot_0001" />

- remap a topic (

camera/image_raw -> kinect/image_raw):

<node name="camera_driver" pkg="ros_parameters" type="camera_node_0" ns="robot_0001">

<remap from="camera" to="kinect" />

</node>

So we can change any ROS resource name as we please, such that we adapt a node to any given system. But that’s enough with portability. It’s time to understand parameters now.

Parameters

Let’s take a look at the camera_node_0 code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

class CameraNode {

public:

CameraNode() {

logger_prefix_ = ros::this_node::getName() + ": ";

// Initialize publisher

ros::NodeHandle camera_nh(nh_, "camera");

it_ = std::make_shared<image_transport::ImageTransport>(camera_nh);

img_publisher_ = it_->advertise("image_raw", 1);

// Read image

std::string pkg_path = ros::package::getPath("ros_parameters");

cv::Mat image = cv::imread(pkg_path + "/data/image.jpg", cv::IMREAD_COLOR);

if (image.size().area() == 0) {

ROS_FATAL_STREAM(logger_prefix_ << "Failed to read source image");

return;

}

// Initialize message

image_msg_ =

cv_bridge::CvImage(std_msgs::Header(), "bgr8", image).toImageMsg();

image_msg_->header.frame_id = "camera_link";

// Start publish loop

img_timer_ =

nh_.createTimer(ros::Rate(30), &CameraNode::imgTimerCallback, this);

ROS_INFO_STREAM(logger_prefix_ << "Node is initialized");

}

private:

void imgTimerCallback(const ros::TimerEvent& /*event*/) {

image_msg_->header.stamp = ros::Time::now();

img_publisher_.publish(image_msg_);

}

std::string logger_prefix_;

ros::NodeHandle nh_;

ros::Timer img_timer_;

std::shared_ptr<image_transport::ImageTransport> it_;

image_transport::Publisher img_publisher_;

sensor_msgs::ImagePtr image_msg_;

};

If we look carefully, we’ll notice that there are a few hardcoded values. Take, for example, the publish rate of the /camera/image_raw topic. It’s set to 30 Hz. But what if we wanted to change it to 50 Hz? Then we would have to change the number in line 26, recompile the code and relaunch the node. And what if we wanted to set it to 60 Hz? Then we’d make the change and recompile the code once again. Is having to go through this process every time acceptable? You could say “whatever, I’m fine with it!”. There are many arguments to be made here, but let’s consider one of them for now. Let’s say we want to launch the node multiple times and each instance to have a different publish rate. Then we are stuck. We cannot comply with both frequencies at the same time. It’s at that point when we have to accept the fact that the publish rate is a parameter and we have to treat it as such.

Of course, ROS can help us with this. We can upload the desired rates to the parameter server and have each node instance retrieve its own copy from the server. We can specify the values in a launch file:

<node name="camera_driver_0" pkg="ros_parameters" type="camera_node_1" output="screen">

<param name="rate" value="30" />

<remap from="camera" to="camera_0" />

</node>

<node name="camera_driver_1" pkg="ros_parameters" type="camera_node_1" output="screen">

<param name="rate" value="50" />

<remap from="camera" to="camera_1" />

</node>

and update the code like so:

ros::NodeHandle pnh_("~");

double rate = 30;

if (pnh_.hasParam("rate"))

pnh_.getParam("rate", rate);

else

ROS_WARN_STREAM(logger_prefix_ << "Failed to get rate; defaulting to 30 Hz");

img_timer_ = pnh_.createTimer(ros::Rate(rate), &CameraNode::imgTimerCallback, this);We check if the parameter exists on the parameter server and if so, we grab it. Otherwise, the code assumes a rate of 30 Hz.

We can repeat the same process with as many parameters as we like. But eventually, it becomes impractical having all the parameters laid out inside launch files. It’s much cleaner and elegant putting them in a configuration file and then loading the configuration file in the launch files instead of the parameters one by one. This could be a configuration file:

rate: 30

source_pkg: ros_parameters

source_img: data/ros.jpg

frame_id: camera_link_0

which is then loaded with the rosparam tag in the launch file:

<node name="camera_driver_0" pkg="ros_parameters" type="camera_node_1" output="screen">

<rosparam file="$(find ros_parameters)/config/camera_0_params.yaml" command="load" />

<remap from="camera" to="camera_0" />

</node>

To verify that everything is as expected, we can run

> rostopic hz /camera_0/image_raw

to get the publish rate, or

> rqt_image_view

to see the published image, or

> rostopic echo /camera_0/image_raw --noarr

to see the frame id.

Dynamic Reconfigure

If that’s becoming a bit much to grasp, hang in there a little while longer as we ask the last question. All the parameters we extracted so far, they were defined during the node initialization and remained constant throughout the lifetime of the node. But what if we wanted to change a parameter during runtime? That is, any time while the node is running. For that, we have dynamic_reconfigure.

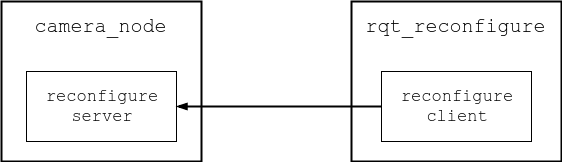

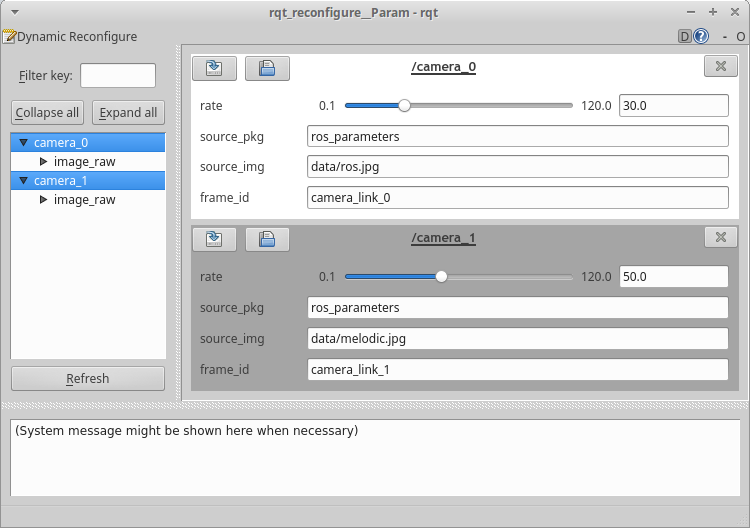

With dynamic reconfigure, a server is created that exposes the parameters to the outside world. Then we can use another program (a dynamic reconfigure client) to get access to the parameters and change their values. Whenever a value is changed, the server is informed and lets the node know of the new value so it can respond appropriately. It’s quite simple to set this up. Firstly, we have to tell the server what the parameters it needs to expose are. For our example, this looks like this:

PACKAGE = "ros_parameters"

from dynamic_reconfigure.parameter_generator_catkin import *

gen = ParameterGenerator()

gen.add("rate", double_t, 0, "Image topic publish rate", 30.0, 0.0, 120.0)

gen.add("source_pkg", str_t, 0, "Source pkg of input image", "ros_parameters")

gen.add("source_img", str_t, 0, "Relative path of input image", "data/ros.img")

gen.add("frame_id", str_t, 0, "Frame id of published images", "camera_link")

exit(gen.generate(PACKAGE, "ros_parameters", "CameraNode"))

You can find more details on how to write such a file here. Then, in the code, all we need to do is initialize the server and define the callback function that will get called every time a parameter is updated. In essence, we just move the initialization code in the constructor to the callback function.

void dynConfCallback(CameraNodeConfig& config, uint32_t /*level*/) {

std::string pkg_path = getSourcePackagePath(config.source_pkg);

std::string filename = pkg_path + "/" + config.source_img;

// Read image

cv::Mat image;

getImage(filename, image);

// Initialize message

image_msg_ =

cv_bridge::CvImage(std_msgs::Header(), "bgr8", image).toImageMsg();

image_msg_->header.frame_id = config.frame_id;

// Update publish rate

img_timer_.setPeriod(ros::Duration(1.0 / config.rate));

img_timer_.start();

}You can take a look at the camera_node_2.cpp source file in the repository for the complete example. Now, we can launch the nodes are before (minus the configuration files):

<node name="camera_driver_0" pkg="ros_parameters" type="camera_node_2" output="screen">

<remap from="camera" to="camera_0" />

</node>

<node name="camera_driver_1" pkg="ros_parameters" type="camera_node_2" output="screen">

<remap from="camera" to="camera_1" />

</node>

Once the nodes are running, we can start rqt_reconfigure and update the parameters as we please…

> rosrun rqt_reconfigure rqt_reconfigure

… the server will be notified, the callback will be called, and the node will update its state. Have you noticed anything different compared to the configuration files example when the nodes start? Both examples allow us to configure a node instance, but in the dynamic reconfigure example, the nodes always take the same default values when they start. So how can we fix this?

One of the ways dynamic reconfigure parameters are communicated is through the parameter server. That means, for every parameter we see in the rqt_reconfigure window, there is a corresponding parameter in the parameter server. The server actually reads the values in the parameter server to initialize itself. So if we set the parameters with a configuration file during launch time as we did before, we should be able to properly initialize the nodes. So let’s add the rosparam tags in the launch file. We have to be careful though because now we should not place the parameters in the private namespace of the nodes. Instead, we should place them in the namespace of the reconfigure server (this namespace is given as an argument in the constructor of the server).

<rosparam file="$(find ros_parameters)/config/camera_0_params.yaml" command="load" ns="camera_0" />

<node name="camera_driver_0" pkg="ros_parameters" type="camera_node_2" output="screen">

<remap from="camera" to="camera_0" />

</node>

<rosparam file="$(find ros_parameters)/config/camera_1_params.yaml" command="load" ns="camera_1" />

<node name="camera_driver_1" pkg="ros_parameters" type="camera_node_2" output="screen">

<remap from="camera" to="camera_1" />

</node>

So we can see that configuration files are complementary to dynamic reconfigure parameters. With the former, we initialize a node, and with the latter, we update the node anytime during its operation.

Conclusion

I hope I’ve demonstrated vividly enough how important parameters are to structuring a node and defining its usability. It’s not just about convenience. When we create a node and we intend to release it to the public, we have to make sure it’s usable by others by giving them the opportunity to modify it according to their specific needs.

This has been the typical use of parameters, but there is much more power in them. We cannot only use parameters to modify the operation of a node, but we can also define it altogether! Curious? Wait until the next post.