Let’s continue with the second part of our node parameterization mini-series. This time we look at how we can minimize development effort and maintenance by taking advantage of configuration files. Our working example will focus on setting up devices present in a robotics system. Instead of creating multiple nodes and hardcoding the initialization of specific devices in each one of them, we’ll see how we can create one generic node that can load any number and type of devices. This way we can spawn instances of the same node with different configurations and have them automatically connect, initialize and retrieve data from the specified devices. As always, there is an accompanying repository which you can download and try things yourself.

Introduction

A ROS system is a distributed network of nodes. In other words, it’s a collection of system components, potentially situated in different computers, that communicate with each other in order to exchange information. Some of these nodes are part of the hardware interface and others of what creates the intelligence of the robot. The hardware interface is what connects a high-level node with the real hardware. It’s a fancy way of describing a set of drivers. A driver connects to a communication bus, talks to one or more devices and creates an interface, i.e. topics and services, such that data from the devices are pulled into the ROS network and commands from the ROS network reach the devices. So let’s see one way we can set up such devices.

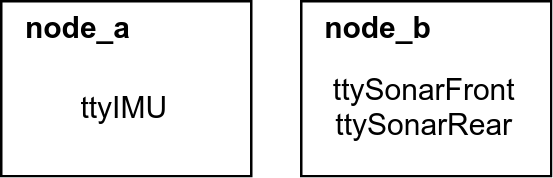

We are going to create a few hypothetical devices so that we have something to work with during this process. We’ll use a utility to create 3 virtual serial ports with the names ttyIMU, ttySonarFront and ttySonarRear. One node will be responsible for the first one of them and another node for the last two. “Why not have one node for all three devices?”, you ask. For the sake of this example, let’s assume that one of the devices is on one computer and the other two are on a second one.

The nodes will read from the serial ports and publish their data on a topic. They will also monitor their state and publish diagnostic statuses. If you don’t know what ROS diagnostics are, you can read more about them here.

Preparation

We’ll use socat (a tool that establishes byte streams) for creating the virtual serial ports. So first, let’s install it:

> sudo apt install socat

Then we run

> mkdir ~/dev

to create a directory in our home folder. This is where the serial ports will appear. Now we can set up the ports with socat:

> socat -d -d pty,raw,echo=0,link=/home/`whoami`/dev/ttyIMU pty,raw,echo=0,link=/home/`whoami`/dev/ttyIMU0 &

> socat -d -d pty,raw,echo=0,link=/home/`whoami`/dev/ttySonarFront pty,raw,echo=0,link=/home/`whoami`/dev/ttySonarFront0 &

> socat -d -d pty,raw,echo=0,link=/home/`whoami`/dev/ttySonarRear pty,raw,echo=0,link=/home/`whoami`/dev/ttySonarRear0 &

We should be able to see 6 ports in the directory we created above:

> ls ~/dev

ttyIMU ttyIMU0 ttySonarFront ttySonarFront0 ttySonarRear ttySonarRear0

How this works is that we write to one port [tty<X>0] and we read from the other one [tty<X>]. Lastly, let’s create a loop that will continuously write to the serial ports so that we have something to read later from our nodes:

> while true; do

> echo "Hello from Imu: $RANDOM" > ~/dev/ttyIMU0;

> echo "Hello from SonarFront: $RANDOM" > ~/dev/ttySonarFront0;

> echo "Hello from SonarRear: $RANDOM" > ~/dev/ttySonarRear0;

> sleep 0.02; # 50 Hz

> done

We can check that data are actually written to the serial ports with the following command:

> cat < ~/dev/ttyIMU

Let’s also install a C++ ROS library for interfacing with serial ports:

> sudo apt install ros-${ROS_DISTRO}-serial

Before we continue, if later, for any reason, you stop getting messages published from the nodes, kill the streams with

> killall socat

and run the socat commands again to reinitialize the serial ports.

Design

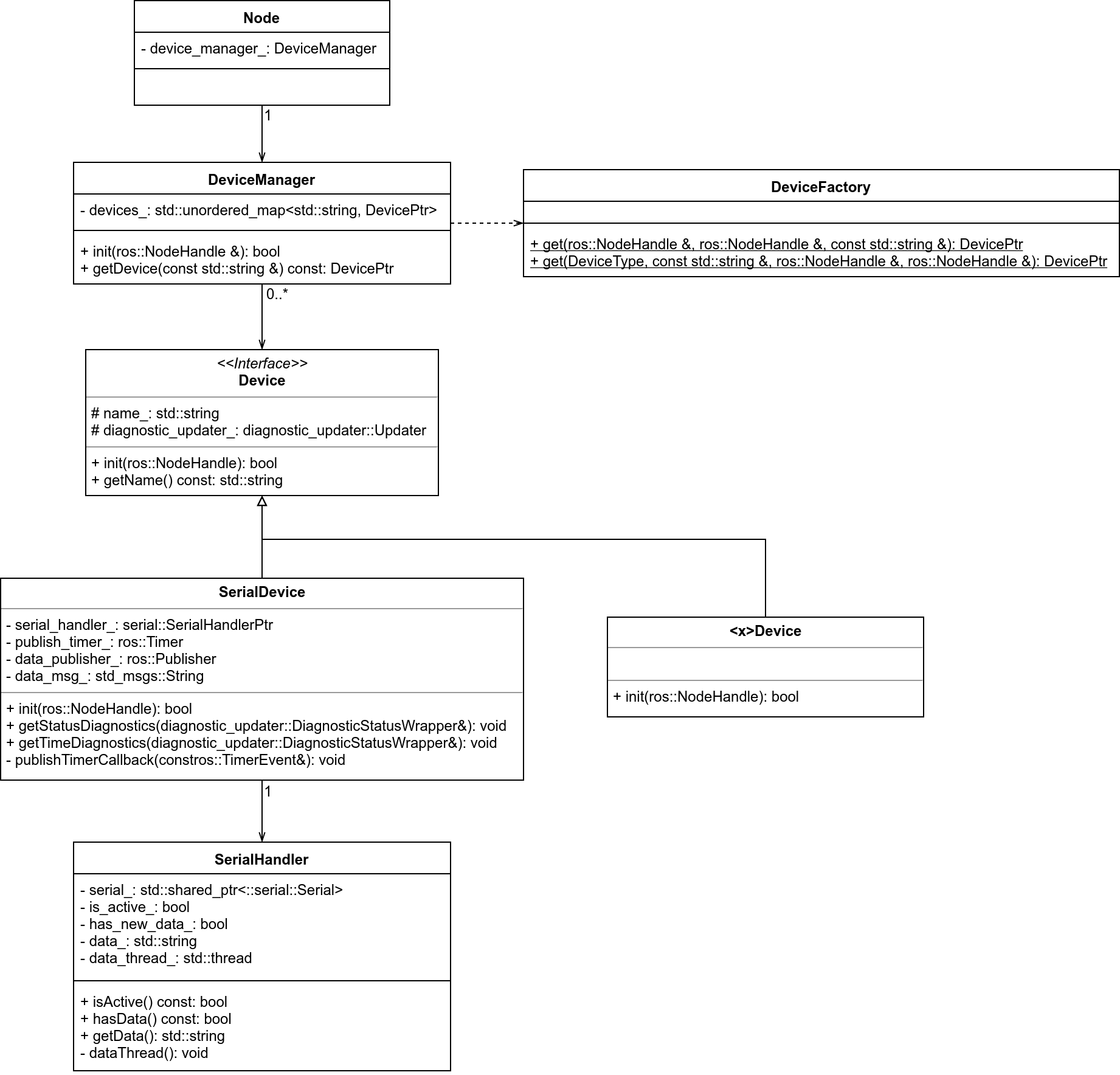

We’ve set up our (virtual) hardware and now it’s time to pull its data into ROS. How do we do this? We have to prepare a design and in order to do that, we need to specify requirements. We’ll assume different entities and assign roles to them, effectively encapsulating different pieces of logic. This is what it could look like:

- We want to have a node that creates and owns a device manager

- The node provides the namespace from which the device manager will read what devices it needs to create

- We want to have a device manager that maintains a list of devices

- When a device is to be created, the manager provides the namespace from which the device will read its own configuration

- We want to have a device factory which given a device type, it creates a device of that type, initializes it and returns it

- We want to have a device interface that defines how implementations of devices should look like

- We want to have device specializations for different device types that implement their logic

- A device connects to its hardware, initializes it, pulls and publishes its data

- A device monitors the state of its hardware and publishes diagnostics

We can see the design in the diagram above. Basically, we have a node that owns a device manager. The node provides the device manager with a namespace from which it will read its configuration. The device manager reads the list of devices and then, one by one, asks from the device factory to create them. The device factory reads the device type, creates an instance of the associated device class, and provides the namespace for the device to read its own configuration and initialize itself. Once initialized, the device grabs the data from the hardware and publishes it on a topic.

Implementation

For the full implementation, please look at the repository. Here, we’ll only go through the most important points.

Launching the nodes now looks like this:

<node name="node_a" pkg="ros_node_configuration" type="devices_node">

<rosparam file="$(find ros_node_configuration)/config/node_a_config.yaml" command="load" />

</node>

<node name="node_b" pkg="ros_node_configuration" type="devices_node">

<rosparam file="$(find ros_node_configuration)/config/node_b_config.yaml" command="load" />

</node>

We spawn the same node twice by providing different configuration files. Here is an example of a configuration file:

devices:

names: [imu]

imu:

type: serial

port: ~/dev/ttyIMU

topic_name: imu

publish_rate: 40

hardware_id: imu

diagnostic_period: 0.2

The device manager reads the list of names under the devices namespace. The configurations of these devices are on the same level as the list of names. So the device manager says to the device factory here is a name for a device and a namespace from which you can read its configuration; please create the device for me. The device factory reads the device type and creates an instance of that type of device. Then it gives the device namespace to the device and kindly asks it to initialize itself. If all goes well, the device is returned to the device manager where it is stored along with the rest of the devices.

Results

If we execute the launch file, we can see that 3 devices are being created:

> roslaunch ros_node_configuration bringup.launch

[ INFO] [1555235587.994927079]: SerialHandler: Opened port /home/nlamprian/dev/ttyIMU

[ INFO] [1555235587.997787139]: SerialDevice[imu]: Initialized successfully

[ INFO] [1555235587.999776285]: SerialHandler: Opened port /home/nlamprian/dev/ttySonarFront

[ INFO] [1555235588.001442668]: SerialDevice[sonar_front]: Initialized successfully

[ INFO] [1555235588.004508451]: SerialHandler: Opened port /home/nlamprian/dev/ttySonarRear

[ INFO] [1555235588.005816399]: SerialDevice[sonar_rear]: Initialized successfully

There are 2 nodes responsible for them:

> rosnode list

/node_a

/node_b

/rosout

Each device is publishing its own data topic:

> rostopic list

/diagnostics

/imu

/rosout

/rosout_agg

/sonar_front

/sonar_rear

When echoing one of these topics, we get data like this:

rostopic echo /imu

data: "Hello from Imu: 14873"

---

data: "Hello from Imu: 24298"

---

Lastly, we can launch the runtime monitor and look at the diagnostic statuses:

> rosrun rqt_runtime_monitor rqt_runtime_monitor

There, we can see 6 statuses coming from the 3 devices. Each device publishes one status about the device health and another one about the topic health.

If we Ctrl+C the write loop we started earlier, errors will appear in the monitor suggesting that messages are not being published anymore. If we further run killall socat, new errors will appear telling us that the devices are down.

Conclusion

The concept of using configuration files for the flexible initialization of entities can be applied to anything we want. In this particular example, what we did is that we mocked devices. In a simulation, we can either formally simulate something and get actual data back, or if we don’t care about the data, but the system still needs to see that a device is present in order to function properly, we can just mock it and have it produce and work on artificial data.

So far, we’ve seen how we can create a device. Once created, the device has a fixed functionality. All instances of the device perform the exact same steps. But what if we wanted to alter these steps, transform or filter the data? Can we remain flexible and still make use of configuration files? We’ll look into these kinds of questions next time.